When?

When?

The when is often the most challenging of any endeavour. Often completely tied up in our own psychology, I'm sure we're all going to resonate with, "This year I'm going to get fit" type goal. The problem is that our pre-contemplative stage is often subconscious and difficult to conceive. We then rush to contemplation. It feels good, so most of us spend a great deal of time contemplating what, how, and when. Launching from here without structure is often disastrous for two reasons; 1. We don't achieve our goal, and are overweight by Easter again, and 2. We feel bad. Whilst some of us cope better with failure than others, sometimes managing to use our cognition to re-frame these to lessons, or reflections on small gains. Others however dwell a great deal on these failures, creating negative feedback loops that crash our dopaminergic reality into the ground profoundly. Sometimes making it very nearly impossible to get out of bed, or get anywhere on-time.

The flip of this notion, would be to create, and become cognisant of these negative loops kicking you in the teeth whilst you lay bare on the ground. Instead, roll over, stand up, and put one foot in front of the other. Before you know it, you did one push up, or burpee depending on your vigor on standing, and you've walked 10m to put your phone on the bench to grab a snack. So, of you could do that, tomorrow you could do 2 push-ups, and walk around the block before the snack. Perhaps before long, the snack turns from a family size bag of flamin-hot Cheetos (my favourite), and into a glass of water, a tea, some fruit, or something else more akin to your goal.

James Clear talks extensively about these things, and I highly recommend reading or listening to his book, "Atomic habits". Linking and stacking habits, focusing on the when, is a key principle of his book, and so very well explained. It's motivational in it's on right, and so I highly expect that when you finish it, you'll be a new you. Even if it's only for a few months.

How then do we sustain change that we've invested in so heavily? Why does failure crush us out of action so intensely? I believe it's because of our innate hedonism. Deriving from ancient Greek, this word means, in essence, to move toward pleasure, and away from pain. Part of our very ethos. Reflecting on this can give you true power. Taking ownership through our struggles, acknowledging our inside voice telling us to not bother, and moving forward is incredibly powerful. As Prof. Andrew Huberman points out, it's almost impossible for the amygdala to fire (causing fear) whilst engaging our forebrain, or practically, moving forward. The combination of mental resources involved in walking or running, makes it very difficult to experience negative thoughts at the same time. Why? Evolutionarily, best guess is that this is because once we've made the decision to run, we devote absolutely every single resource to not being eaten by the lion. Whilst you've undoubtedly heard of the principles of flight, fright, and freeze, this is not the same. I'm talking about taking ownership of those basic human principles, and exploit running, or flight, to launch ourselves from fear. When not strickenly facing something with immediacy, a great many of us can take a moment ordinarily to re-contextualise what's before us in order to increase our chance of success.

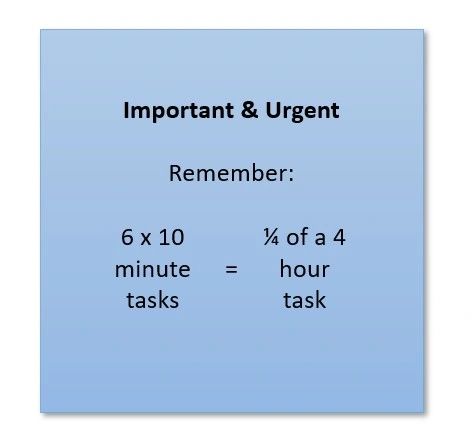

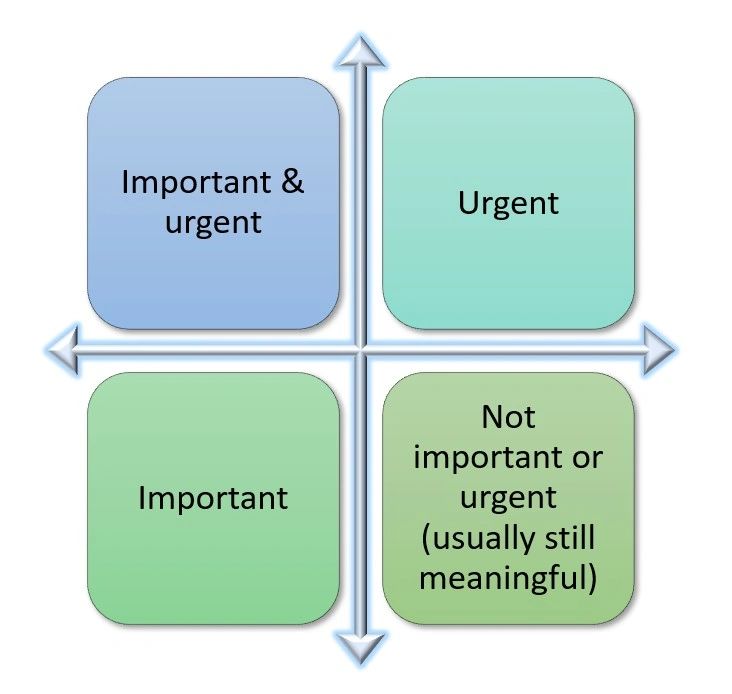

Typically, I've seen people utilise a priority quadrant, see below. Problem with this for me, is that it lends nothing to how to juggle both short and long tasks. See, two tasks may be assessed of equal importance both on value and time priority, but one will take 5 minutes, and the ither 4 hours. I can say with almost certainty that everybody will complete the 5 minute task first. Why? Hedonism. That feeling of Serotonin or perhaps dopamine is what we all want desperately.

Shift this logically. Say you had 50 important tasks of 5 minutes each, and still one 4 hour task. I'm still going to say that the majority of you will set on completing all 50 before commencing the larger task. In reality for many workers, this means that your email inbox dominates your day, and moving away from this dominance takes discipline, respect, but a great deal of diligence.

Practically I would suggest the following:

Plan for random interruptions in your day. You know your job, but think about how much you 'need' to reserve for the unplannable, so you be be responsive. For me it's 2 hours a day.

Plan time to think or reflect. You could even meditate, or learn something. This equates to 39 minutes a day for me.

Plan for 30 minutes for lunch. Loosely ensure meetings don't go over lunch unless you actually want to share food. Running on empty isn't ideal for good outcomes.

Turn off email notifications on your computer and your phone. Set it so that you must go into your email app to receive emails. For the hyper important, you can set exceptions to force alerts from some senders if your savvy.

Break those big 4 hour tasks up into sections. We all can work solidly for around 45 minutes before needing a break. Don't fight this. Factor it into your work day. Set hour long focused time frames throughout your day and across your week to get this done.

If you have to wrote notations attaches to your tasks, such as phone calls. Get savvy at following up with an email to confirm or factor the time to notate into whatever appointments you keep in your calendar.

Do not start a task until you finish another... let's be real, we all do this and that's okay. It's human nature especially when the task before us is boring. We move back to shorter easy tasks because of... hedonism, you guessed it! Notice this forgive yourself but get good at moving things around and exercising discipline.

The real key to falling into the trap of doing all the small, easy things, is to chunk tasks into manageable pieces. Over a short time frame of self-development, you'll actually start to note that you can fit more and more into the 'chunks', meaning in reality that you're more motivated and working harder, whilst capitalising on your dopaminergic experiences and hopefully smiling as a result. That last part is key. I'll discuss mindfulness another time, but don't undervalue the small upturned corner of your lips when you send off a huge task, or that grin as you tick the done box on your task tracking app. It's priceless, and reinforcing all the while.

Deciding what to do, and setting about how and when is key to achieving your goals no matter how small. Remember you're in charge, and how you frame things is in your control. As Jocko Willink would say, "Take ownership, prioritise and execute".

Take care,

Tom

This week's literature review

This week I've read a few journal articles around education. Although the normal pedagogy of Western society illudes my expertise, I have noticed something worth sharing. A recent Finnish study examined the foster care cohort and found that implementation of a particular model was significant at lifting grades, and even the IQ of the target group compared with the general population. This is astounding. IQ in particular, is very well researched and quite crystallised in its formation. Here however, we have an effect that's attributed to the model, but I have pondered an different hypothesis.

In the study, as well as my inductive observations more locally in my own work, I observe that the implementation of any 'model' is typically in a one-on-one setting with kids. What I can also tell you is what I've had reinforced with my reading of the expert Gabor Maté's work on trauma and attachment; that the more people are traumatised, the more connection they crave. The panacea in some large sense, is meaningful attachment. Is it just possible that through the connection of a mentor, even though it's seemingly meaningless to most, that real gains can be made? As the brain calms, neural growth may very really be able to occur. This could in a very practical sense, attribute to significant IQ gains.

Practically, my take away here is to double down on one of my priorities; relationships. By creating opportunity for real connection, you may forge real life-altering growth.

Eiberg, M., & Scavenius, C. (2023). Striving to thrive: a randomized controlled trial of educational support interventions for children in out-of-home care. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 1-24.

Comments

Post a Comment